A police informant reported a horde of vegetable roots drying in the sun outside a home in Randolph County, WV. This is not the kind of news that makes headlines or pricks up ears, but to our friend, a law enforcement officer at the Department of Natural Resources, it was a vital piece of intelligence. That was in the 1980s, soon after the West Virginia Legislature passed a law banning the harvest of wild ginseng except between September and November by permit or with the landowner’s agreement. The officer flew a helicopter to spy with binoculars over the backyard of the suspect’s home. Sure enough, there was a golden heap of uncertified roots and rhizomes two months ahead of the “seng” season. The ginseng buyer busted, he had his booty confiscated and was charged with a heavy fine, but the sengers (poachers) who dug in the forest laid low.

If you watch Appalachian Outlaws (The History Channel, 2014) you might imagine our forest tracks blink with red and blue lights and the mountains echo to sirens and gunfire. In the first episode of the series (all I had patience for between incessant ads), a poor mountain man, Greg Shook, heads out of Georgia for the moist, rich soils on the north sides of West Virginia’s mountains where he heard there is plenty of seng. He evades landowners in private woods and stalks federal lands, stumbling into an illegal grove of cannabis where he narrowly avoids getting shot. With luck, he will dig enough seng to sell to kingpin Tony Coffman or the incomer Corby “The General” Patton. If the story convinces you that outlaw sengers lead thrilling lives fleeing from threat to peril, you will be disappointed to hear from our friend who told me it is a gross perversion of reality, even by the low standards of reality TV.

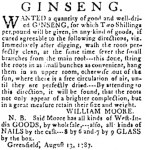

Seng has been harvested from American forests since colonial days, and for time immemorial by native tribes. It supported a thriving export industry to China in the 19th century, and still supplements local incomes. Since Asian ginseng became virtually extinct in the wild, the variety growing along the Appalachian chain is now heavily picked. In our county alone (Pocahontas) 259 lb was declared last year (2015) out of 8,103 lb throughout the state. The average price that year was $410 per lb, and in some years it rises above $700.

No wonder our neighbors keep secret the whereabouts of ginseng. It crouches low on the woodland floor with four or five of five “prongs” reminiscent of beech leaves, and now, in the midst of seng season, a small bunch of red berries catch the eye at the center of the rosette. When sengers dig up swollen rhizomes and filamentous roots they discard the green top and bury the berries under leaf litter to generate new plants. But they never come back the next year because ginseng takes a long time to mature, and harvesting plants under five years old is illegal. I know of no other small woodland plant that is longer-lived: those evading the senger can outlive him, and their longevity is not much less than some trees. As a general rule of nature, plants or animals that grow slowly, mature late and age gradually are not very productive—they don’t need to produce seeds quickly or abundantly to sow posterity because time is on their side. Their strategy worked well until human harvesters came along and stripped entire slopes of these precious vegetables.

Ginseng’s reputation for promoting human longevity, endurance and sexual potency started in China, like so many other ancient notions and philosophies. But does it hold up in an age of science? Hard evidence is hard to find, although there are over 7,000 research/ review articles listed in PubMed. Admittedly, most papers are published in obscure journals based on animal studies or in vitro experiments, and the rare clinical trials of any worth struggle to raise ginseng out of the basket of “alternative therapies” to the shelves of conventional medicine. Like research on other “botanicals,” there is too little attention to batch variation and potential toxicity.

Most serious scientific attention on this plant is focused on saponins (“ginsengosides”), complex, steroid-like molecules which are so-called because shaken in water they make froth. The anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and immunostimulatory activity found under lab conditions suggest that ginseng might render some beneficial effects on our physiology and pathology after eating it fresh or steamed, and at the very least I expect it blesses the hearts that believe in it. Its very name has a healthy glow, even at the end of a “ginseng cigarette” (though healthy cigarettes sound like an oxymoron and may not contain the said herbal).

It takes its name from Schinseng, meaning in Chinese “essence of the earth in the form of man.” If you stretch your imagination, the baggy rhizomes look somewhat like the body and legs of a man. Many old cultures have interpreted in nature divine signs created for our good, like red centaury (for purifying the blood), toothwort (looking like a tooth for toothache), and so on. Dr. Paracelsus popularized these beliefs handed down from Galen, and they persist as folk remedies and in alternative medicine. All I can say after quickly reviewing the science is that ginseng probably does no harm, which is the elementary ethic of healthcare (primum non nocere), but as for doing good and extending our lifespan, the jury is out.

I saw an old man climbing our slopes towards a plateau on Middle Mountain carrying a trowel and a knapsack under his arm. As he bent to dig in the soil, his shaggy, grey beard flowed over the collar of a heavy green coat which had a hole under an arm. I stood watching, wondering.

There are three categories of needs and wants in our lives. First and foremost is the need for something to love, which should be free, and I pondered whether the old man’s love was for our woods and mountains where he roamed as a boy. The second is our need for water and healthy food, which should always be available and affordable, and I guessed from his appearance that he was poor, if not starving. Last and of least importance is our want for luxuries, which are more expensive than the rest but unneeded, and I mused that the forest-gatherer hoped to make a little profit to bring some joy home, perhaps for a nip of whiskey before bedtime or a cheap gift for his family. I could have challenged him because he was trespassing in our woods when the season for ginseng was out, but instead I waved.