There is something magisterial about the biggest living things on Earth. We are the most intelligent, the most prolific, and the most polluting species but we don’t tower in height over everyone. We look up at some animals and plants while they look down on us.

I regret we missed the iconic megafauna that became extinct in the late Pleistocene era. Modern humans arrived a day too late on a geological time scale. I mean woolly mammoths and mastodons, dodos and moas, giant sloths and dire wolves. But I’m thankful we have a few survivors, mostly oceanic leviathans and two species of elephants.

Does any other creature look as imperial as an elephant? They fascinate us and our children fall in love with them from picture books and the telling of stories, particularly in India. At the zoo, we cannot pass the elephant enclosure without stopping. The perfume of aromatic manure guides us by the nose more surely than eyeing a signpost. There is only one grotesque aspect of elephants—a trophy head with tusks hanging on a wall.

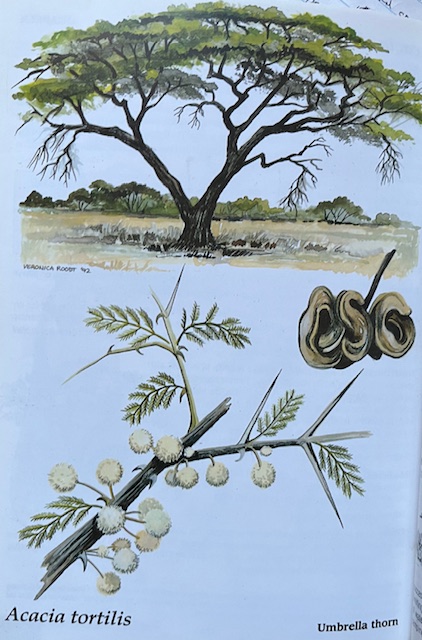

I recently had the thrill of watching hundreds of wild African elephants in their northern Kalahari homeland. They barged through dense bush, like bulldozers and pulled down trees faster than a chainsaw before dining on foliage. They hung around waterholes to suck gallons of water and sprayed dirt on their backs through multifunctional trunks. Family groups marched at a stately pace across the veld in disciplined lines, keeping to the narrow tracks made by generations of heavy feet compressing the sand. My local Penduka guide regarded them respectfully, and so we backed off when they flapped their ears at us. Last month, an angry elephant killed a tourist in Zambia by overturning her vehicle.

Their distrust of human beings is understandable. We imperiled them by poaching, trophy hunting and anthrax from livestock farming. These threats remain but their numbers have rebounded since banning ivory sales and hunting trophies. Botswana’s government should be praised for beefing up anti-poaching units. However, it has resumed issuing hunting quotas since 2019 in response to complaints about an elephant population explosion, now estimated at 130,000, more than in any other country.

The President of Botswana receives complaints from rural people whose livelihoods and even lives are lost from trampling under big beasts. But consider the elephants’ point of view. The finest remaining wilderness is under pressure for agriculture and who can resist the begging image of a hungry child? Partly from their habitat shrinking, powerful animals are losing their fear from habituation, which leads to conflict with humans. I admit foreign visitors like me are part of the problem. Do we love wildlife too much for its good?

Mr. President faces a dilemma. Selling licenses to hunters helps to control the elephant population and top up the Treasury’s coffers. On the other hand, African wildlife has influential foreign advocates who condemn trophy hunting and might boycott safaris where the grisly business continues. He offers surplus animals to neighboring countries and makes an idle threat to send thousands to Germany. Why doesn’t he imitate the Kruger National Park in South Africa where an immunocontraceptive program controls the elephant population?

The mission of preserving biodiversity in pristine lands gets tougher from the direct and indirect impacts of spiraling human numbers. That problem has gotten a lot worse since the 1960s when the United Nations raised publicity. Ironically, Western countries are becoming more pronatalist from worrying about the demographic shift that projects a deficit of young people to support aging populations in the future. Developing countries rankle at criticism and rightly point out that wealthy countries are mainly responsible for plundering natural resources. Politicians grapple with national priorities or bow to resistance.

Meanwhile, elephants will always be elephants and we will decide their fate in our interests. Tant pis! They wouldn’t present such a problem if they weren’t so large, but if we genetically engineered mini elephants as replacements would they inspire as much awe in children at the zoo?