At one time all scientists were amateurs. Most were gentlemen with private incomes like Charles Darwin or clergymen like the Rev. Gilbert White whose church stipend enabled him to spend spare time rambling in the Hampshire countryside. There was a rich crop of these men too among the founding fathers of America: Benjamin Franklin discovered electrical activity in thunderstorms by flying a kite, and Thomas Jefferson created an almanac by recording the weather for nearly fifty years. Today we call them citizen scientists, and after science became a paid profession they continue to flourish where many eyes are needed for collecting “big data.”

One of those sciences is astronomy, which was so memorably presented on BBC TV by Patrick Moore (1923-2012), and for which other amateurs are credited with discovering new exoplanets. Another is ornithology because birders supply tons of data to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the Audubon Society, and the British Trust for Ornithology. And the third—ever since Jefferson—is meteorology.

Years of recording temperatures and rainfall at Monticello helped him to plan the dates for planting crops in his garden. The data were also useful in the patriotic cause of proving the superiority of the Virginia climate compared to Paris where he lived at one time (there was no contest with London weather). In those times climate was thought to be fixed at a given place, just as the continents were believed to be immovable and species immutable.

Mark Twain wrote, Climate is what we expect, weather is what we get. But today the opposite is true because we no longer know what the future climate holds, and we have a firm expectation that weather will always be capricious. More than ever, climate scientists and weathermen/women depend on data from volunteers for modeling the atmosphere for days or even decades ahead.

Jefferson would have drooled at the equipment that is now available to backyard meteorologists. A starter weather station includes a thermometer, barometer, anemometer, hygrometer, and wind vane, but some really sophisticated equipment is affordable. The data can be uploaded to networks like Weather Underground which has more than 32,000 active stations worldwide. All data points are valuable because weather is local, and they contribute to a growing understanding of climate change.

You can join a network for the cost of a customized rain/ hail/ snow gauge ($30). This isn’t glamorous science like measuring glacier retreat, Arctic sea ice, or even sea levels and temperature, but data from your own backyard will be pooled with thousands of other observations for professional analysis.

Naturalists contribute data from monitoring wildlife and flora, which is called phenology. We are warned that if a warming trend continues the return dates of birds and butterflies that winter in warmer climes will be earlier, and they will breed further north. Hummingbirds arrived in Williamsburg today (April 12), but future generations may see them in March or even staying the year round.

Budburst is a phenology project for volunteers to record when trees and plants flower. A  Yoshino cherry tree in our yard bloomed the very same days this year as last, but we can’t assume the same in the future because this species is highly sensitive to temperature. Researchers in Seattle predict that cherry blossom will reach its peak 5-13 days earlier in Washington DC by 2050 than today (estimates vary depending on carbon emissions). If so, the National Cherry Blossom Festival and Parade will have to move forward to March.

Yoshino cherry tree in our yard bloomed the very same days this year as last, but we can’t assume the same in the future because this species is highly sensitive to temperature. Researchers in Seattle predict that cherry blossom will reach its peak 5-13 days earlier in Washington DC by 2050 than today (estimates vary depending on carbon emissions). If so, the National Cherry Blossom Festival and Parade will have to move forward to March.

It’s hard to say whether natural signs or physical measurements are the more reliable guides to the climate, but temperature and rainfall have the longest records. The first frost dates in fall have been recorded in Williamsburg for over a century. Lately they have been getting later, and the growing season of frost-free days between spring and fall is correspondingly longer. The number of days when temperatures fell below freezing have declined by 20 days over the same period (notwithstanding the recent cold winter), which harmonizes with old stories when people drove across the frozen York River and skated on ponds.

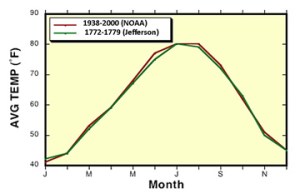

It seems a contradiction then that average temperatures here in the hottest month of the year (July) are unchanged since records began in 1895 (78°F/ 25.5°C). Summer temperatures in Monticello (100 miles west) have also remained the same as when Jefferson recorded them, and it’s much the same story for rainfall. This leads people to wonder if the climate is really changing.

But note the huge variances in the data. Our rainfall in July, which averaged 5 inches over the past 120 years, has a range of between 1 and 13 inches. You need data over a long period to prove a consistent trend in average temperature and rainfall with this statistical noise. But there have been more exceptionally hot days in summer here as elsewhere, and this may be the warning signal. We are so accustomed to paying attention to averages and medians (50 percentiles) that we can overlook the significance of outliers. I was reminded after an old cabin was taken down recently in the Allegheny Mountains when I was shown where the builder had scrawled in the joint between logs: June 6th 1878 frost killed beans.

Farmers and gardeners have always dreaded late freezes and heat waves, but if the climate becomes more dominated by freak weather we too will have something to groan about, and much more than scant snow on the piste or scorching sun on the barbecue. Amateur scientists today stand in a long tradition, but they are a different bunch to the gentlemen of yore who were led by private curiosity into the field. Today’s efforts by legions of volunteers are often propelled by a hope that through understanding nature we can better preserve it.

Next Post: Fertility Preservation